Anatomy of an Improv Scene & Other Stuff

Yesterday was my last class for Improv 3, as I'll be missing the final two classes due to my upcoming visit to India for Diwali (and my birthday!). I'm really going to miss it, but I also need a break. I don't think I've taken much time off this year, so I really need to be mindful about prioritizing some downtime. Maybe that should be a New Year's resolution? I'm also torn between taking Improv 4 or repeating Improv 3, since I'll miss the first two classes for the next term. I'm leaning toward repeating because I feel like I still have a lot to learn when it comes to scene work, but at the same time, I'll really miss working with my classmates. :(

At this point, this blog is kind of becoming a public notebook of what I'm learning, which I guess is a good thing. Also, it allows me to be vulnerable, which, if I'm being honest, can be a bit scary.

Now onto some stufff we learned yesterday.

One of the very first things we discussed in class was the idea of avoiding conflict. Why? Because sometimes conflict leads nowhere (which is a great life lesson, now that I think about it) and doesn't advance the scene. Here's an example:

"I got a new dog."

"Yes, but it's clearly too large for you!"

vs

"I got a new dog."

"No, you didn't. I don't see a dog. You f**king suck at this."

One of these responses moves the scene forward, and the other stops it in its tracks. If the "no dog" bit isn't funny, the scene is dead.

Another example I remember from class: We were doing quick scenes with our partners, and I pretended to be a window cleaner (I think?) and started with the physicality of cleaning. My partner joined in as a fellow cleaner and started throwing things around. Here's how the conversation went:

Me: "What are you doing?"

My partner: "I'm throwing stuff around. Think about it—if I keep throwing stuff and you keep cleaning, we'll both get to keep our jobs!"

I could have replied, "That's not good. You're supposed to clean." But that doesn't do much for the scene.

Instead, I said: "Oh yeah, good idea. Let's make sure we both stay employed." That response moved the scene forward.

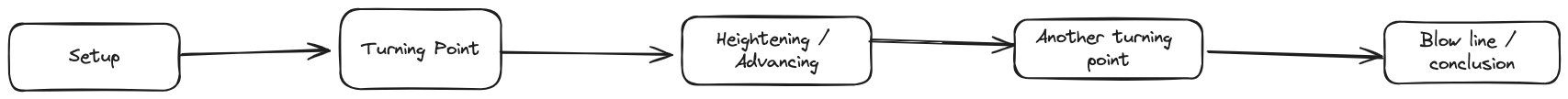

We also discussed the anatomy of an improv scene. It's essentially about how a scene should be structured. Here's a rough flowchart I made from a picture we took in class:

So, in story form, this setup could look like the following (I remember coming up with this story from an exercise we did):

Setup:

There once was a guy named Adam, and he had a dog named Waffles. One morning, he took Waffles for a walk.

Turning point:

While on the walk, Waffles broke his leash and ran away. Adam frantically tried to get Waffles back.

Heightening:

Searching for Waffles, Adam ended up in an alley where he saw a robber who had Waffles with him.

Another turning point:

Adam confronted the robber, and the robber demanded a ransom in exchange for Waffles. Adam said he didn't have any money on him but could e-transfer the ransom. The robber agreed.

Blow line:

Adam had an idea. He looked at the robber and said, "I'm sending it now—what's your email address?" The robber replied, "[email protected]."

Adam smirked and hit "send." A few seconds later, the robber's phone buzzed. But instead of receiving payment, the robber was confused to see a PayPal request for a donation to the local dog shelter. While the robber was distracted, Waffles slipped free and bolted back to Adam. Before the robber could react, Adam and Waffles sprinted away, laughing as they made their escape.

Again, this isn't a hard-and-fast rule, but I think it helps give structure to the scene.

Oh, and another thing we talked about—adding too many characters to a scene can confuse the audience. It's usually better to reuse the existing characters or setup.

A lot of stuff, eh? I know, but hopefully, with practice, it will get better. Here's to more of this!